A brief review of Korean Buddhim

Korean Buddhism is distinguished from other forms of Buddhism by its attempt to resolve what it sees as inconsistencies in Mahayana Buddhism.

According to Wikipedia and various Korean reference materials, early Korean monks believed that the traditions they received from foreign countries were internally inconsistent.

To address this, they developed a new holistic approach to Buddhism.

This approach is characteristic of virtually all major Korean thinkers, and has resulted in a distinct variation of Buddhism, which is called Tongbulgyo ("interpenetrated Buddhism"), a form that sought to harmonize all disputes (a principle called hwajaeng 和諍) by Korean scholars.

Korean Buddhist thinkers refined their predecessors' ideas into a distinct form.

As it now stands, Korean Buddhism consists mostly of the Seon Lineage, primarily represented by the Jogye and Taego Orders.

The Korean Seon has a strong relationship with other Mahayana traditions that bear the imprint of Chan teachings as well as the closely related Zen.

Other sects, such as the modern revival of the Cheontae lineage, the Jingak Order (a modern esoteric sect), and the newly formed Won, have also attracted sizable followings.

Korean Buddhism has contributed much to East Asian Buddhism, especially to early Chinese, Japanese, and Tibetan schools of Buddhist thought.

When Buddhism was originally introduced to Korea from Former Qin in 372, about 800 years after the death of the historical Buddha, shamanism was the indigenous religion.

As it was not seen to conflict with the rites of nature worship, Buddhism was allowed by adherents of Shamanism to be blended into their religion.

Thus, the mountains that were believed by shamanists to be the residence of spirits in pre-Buddhist times later became the sites of Buddhist temples.

Though it initially enjoyed wide acceptance, even being supported as the state ideology during the Goryeo period, Buddhism in Korea suffered extreme repression during the Joseon era, which lasted over five hundred years.

During this period, Neo-Confucianism overcame the prior dominance of Buddhism.

Only after Buddhist monks helped repel the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–98) did the persecution of Buddhists stop.

Buddhism in Korea remained subdued until the end of the Joseon period, when its position was strengthened somewhat by the colonial period, which lasted from 1910 to 1945.

However, these Buddhist monks did not only put an end to Japanese rule in 1945, but they also asserted their specific and separate religious identity by reforming their traditions and practices.

They laid the foundation for many Buddhist societies, and the younger generation of monks came up with the ideology of Mingung Pulgyo, or "Buddhism for the people." The importance of this ideology is that it was coined by the monks who focused on common men's daily issues.

After World War II, the Seon school of Korean Buddhism once again gained acceptance.

A 2005 government survey indicated that about a quarter of South Koreans identified as Buddhist.

However, the actual number of Buddhists in South Korea is ambiguous as there is no exact or exclusive criterion by which Buddhists can be identified, unlike the Christian population.

With Buddhism's incorporation into traditional Korean culture, it is now considered a philosophy and cultural background rather than a formal religion.

As a result, many people outside of the practicing population are deeply influenced by these traditions.

Thus, when counting secular believers or those influenced by the faith while not following other religions, the number of Buddhists in South Korea is considered to be much larger.

Similarly, in officially atheist North Korea, while Buddhists officially account for 4.5% of the population, a much larger number (over 70%) of the population are influenced by Buddhist philosophies and customs.

Buddhism in the Three Kingdoms:

When Buddhism was introduced to Korea in the 4th century CE, the Korean peninsula was politically subdivided into three kingdoms: Goguryeo in the north (which included territory currently in Russia and China), Baekje in the southwest, and Silla in the southeast.

There is concrete evidence of an earlier introduction of Buddhism than traditionally believed. A mid-4th century tomb, unearthed near Pyongyang, is found to incorporate Buddhist motifs in its ceiling decoration.

Korean Buddhist monks traveled to China or India in order to study Buddhism in the late Three Kingdoms Period, especially in the 6th century. In 526, The monk Gyeomik from Baekje traveled via the southern sea route to India to learn Sanskrit and study the Vinaya.

The monk Paya (562–613?) from Goguryeo is said to have studied under the Tiantai master Zhiyi. Other Korean monks of the period brought back numerous scriptures from abroad and conducted missionary activity throughout Korea.

Several schools of thought developed in Korea during these early times:

the Samlon (三論宗) or East Asian Mādhyamaka school focused on Mādhyamaka doctrine

the Gyeyul (戒律宗, or Vinaya in Sanskrit) school was mainly concerned with the study and implementation of śīla or "moral discipline"

the Yeolban (涅槃宗, or Nirvāna in Sanskrit) school based in the themes of the Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra

the Wonyung (圓融宗, or Yuanrong in Chinese) school formed toward the end of the Three Kingdoms Period. This school lead to the actualization of the metaphysics of interpenetration as found in the Avatamsaka Sutra and was considered the premier school, especially among the educated aristocracy.

the Hwaeom (華嚴宗 or Huayan school) was the longest lasting of the "imported" schools. It had strong ties with the Beopseong (法性宗), an indigenous Korean school of thought.

The date of the first mission from Korea to Japan is unclear, but it is reported that a second detachment of scholars was sent to Japan upon invitation by the Japanese rulers in 577.

The strong Korean influence on the development of Buddhism in Japan continued through the Unified Silla period. It was not until the 8th century that independent study by Japanese monks began in significant numbers.

Goguryeo period:

In 372, the monk Sundo (順道, pinyin: Shùndào) was sent by Fu Jian (337–385) (苻堅) of Former Qin to the court of the King Sosurim of Goguryeo. He brought texts and statues (possibly of Maitreya, who was popular in Buddhism in Central Asia), and the Goguryeo royalty and their subjects quickly accepted his teachings.

Buddhism in China was in a rudimentary form, consisting of the law of cause and effect and the search for happiness. This had much in common with the predominant Shamanism, which likely led to the quick assimilation of Buddhism by the people of Goguryeo.

Early Buddhism in Silla developed under the influence of Goguryeo. Some monks from Goguryeo came to Silla and preached among the people, making a few converts.

In 551, Hyeryang (惠亮), a Goguryeo monk was appointed the first National Patriarch of Silla. He first presided over the "Hundred-Seat Dharma Assembly" and the "Dharma of Eight Prohibitions".

Baekje period:

In 384, the Indian monk Marananta arrived in Baekje and the royal family received the strain of Buddhism that he brought.

King Asin of Baekje proclaimed, "people should believe in Buddhism and seek happiness." In 526, the Baekje monk Gyeomik (겸익, 謙益) traveled directly to Central India and came back with a collection of Vinaya texts, accompanied by the Indian monk Paedalta (Sanskrit: Vedatta).

After returning to Baekje, Gyeomik translated the Buddhist scriptures in Sanskrit into seventy-two volumes.

The Gyeyul school in Baekje was established by Gyeomik about a century earlier than its counterpart in China. As a result of his work, he is regarded as the father of Vinaya studies in Korea.

Silla period:

Buddhism did not enter the kingdom of Silla until the 5th century.

The common people were first attracted to Buddhism here, but there was resistance among the aristocrats.

In 527, however, a prominent court official named Ichadon presented himself to King Beopheung of Silla and announced he had become Buddhist.

The king had him beheaded, but when the executioner cut off his head, it is said that milk poured out instead of blood.

Paintings of this are in the temple at Haeinsa and a stone monument honoring his martyrdom is in the National Museum of Kyongju.

During the reign of the next king, Jinheung of Silla, the growth of Buddhism was encouraged and eventually recognized as the national religion of Silla.

Selected young men were physically and spiritually trained at Hwarangdo according to Buddhist principles regarding one's ability to defend the kingdom.

King Jinheung later became a monk himself.

The monk Jajang (慈藏) is credited with having been a major force in the adoption of Buddhism as a national religion.

Jajang is also known for his participation in the founding of the Korean monastic sangha.

Another great scholar to emerge from the Silla Period was Wonhyo.

He renounced his religious life to better serve the people and even married a princess for a short time, with whom he had a son.

He wrote many treatises and his philosophy centered on the unity and interrelatedness of all things.

He set off to China to study Buddhism with a close friend, Uisang, but only made it part of the way there.

According to legend, Wonhyo awoke one night very thirsty. He found a container with cool water, which he drank before returning to sleep.

The next morning he saw that the container from which he had drunk was a human skull and he realized that enlightenment depended on the mind. He saw no reason to continue to China, so he returned home.

Uisang continued to China and after studying for ten years, offered a poem to his master in the shape of a seal that geometrically represents infinity. The poem contained the essence of the Avatamsaka Sutra.

Buddhism was so successful during this period that many kings converted and several cities were renamed after famous places during the time of the Buddha.

Unified Silla (668–935):

In 668, the kingdom of Silla succeeded in unifying the whole Korean peninsula, giving rise to a period of political stability that lasted for about one hundred years under Unified Silla. This led to a high point in scholarly studies of Buddhism in Korea.

The most popular areas of study were Wonyung, Yusik (Ch. 唯識; Weishi) or East Asian Yogācāra, Jeongto or Pure Land Buddhism, and the indigenous Korean Beopseong ("Dharma-nature school").

Wonhyo taught the Pure Land practice of yeombul, which would become very popular amongst both scholars and laypeople, and has had a lasting influence on Buddhist thought in Korea.

His work, which attempts a synthesis of the seemingly divergent strands of Indian and Chinese Buddhist doctrines, makes use of the Essence-Function (體用 che-yong) framework, which was popular in native East Asian philosophical schools.

His work was instrumental in the development of the dominant school of Korean Buddhist thought, known variously as Beopseong, Haedong (海東, "Korean") and later as Jungdo (中道, "Middle Way")

Wonhyo's friend Uisang (義湘) went to Chang'an, where he studied under Huayan patriarchs Zhiyan (智儼; 600–668) and Fazang (法藏; 643–712).

When he returned after twenty years, his work contributed to Hwaeom Buddhism and became the predominant doctrinal influence on Korean Buddhism together with Wonhyo's tongbulgyo thought.

Hwaeom principles were deeply assimilated into the Korean meditation-based Seon school, where they made a profound effect on its basic attitudes.

Influences from Silla Buddhism in general, and from these two philosophers in particular crept backwards into Chinese Buddhism.

Wonhyo's commentaries were very important in shaping the thought of the preeminent Chinese Buddhist philosopher Fazang, and Woncheuk's commentary on the Saṃdhinirmocana-sūtra had a strong influence in Tibetan Buddhism.

The intellectual developments of Silla Buddhism brought with them significant cultural achievements in many areas, including painting, literature, sculpture, and architecture.

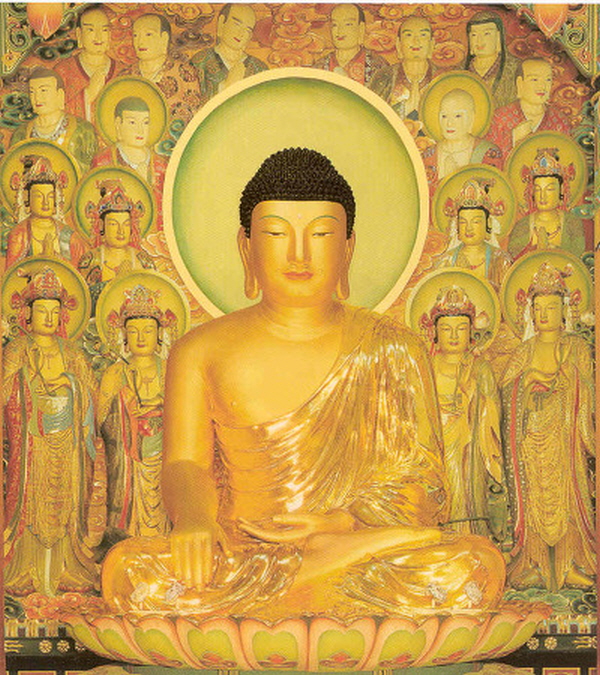

During this period, many large and beautiful temples were built. Two crowning achievements were the temple Bulguksa and the cave-retreat of Seokguram (石窟庵).

Bulguksa was famous for its jeweled pagodas, while Seokguram was known for the beauty of its stone sculpture.

Current situation:

The Seon school, which is dominated by the Jogye order in terms of the number of clergy and adherents, practices disciplined traditional Seon practice at a number of major mountain monasteries in Korea, often under the direction of highly regarded masters.

The Taego order, though it has more temples than the Jogye Order, is second in size in terms of the number of clergy and adherents and, in addition to Seon meditation, keeps traditional Buddhist arts alive, such as ritual dance.

Modern Seon practice is not far removed in its content from the original practice of Jinul, who introduced the integrated combination of the practice of Gwanhwa meditation and the study of selected Buddhist texts.

The Korean sangha life is markedly itinerant for monks and nuns pursuing Seon meditation training: while each monk or nun has a "home" monastery, he or she will regularly travel throughout the mountains, staying as long as he or she wishes, studying and teaching in the style of the temple that is housing them.

The Korean monastic training system has seen a steadily increasing influx of Western practitioner-aspirants in the second half of the twentieth century.

It must be noted, however, that the vast majority of Korean monks and nuns do not spend 20 or 30 years in the mountains pursuing Seon training in a form recognizable to westerners.

Most Korean monks and nuns receive a traditional academic education in addition to ritual training, which is not necessarily in a formal ritual training program.

Those who do spend time in meditation in the mountains may do so for a few years and then essentially return to the life of a parish priest.